As a lover of books and history, I am fascinated by the library collection of Thomas Jefferson. Over six thousand of his books became the Library of Congress. Terribly, in 1851 a fire reduced it to 2,465 volumes, and one-by-one, the Library of Congress has sought to replace the lost books as best they can. But those new acquisitions don’t always bear the mark of Jefferson’s library.

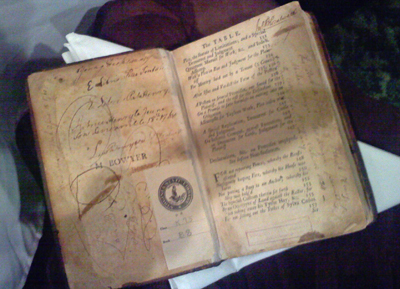

Bookplates, small paper panels glued into the inside cover or first page, were common in the 18th and 19th century. Books were costly treasures, definitely not 99¢, and so owners inserted custom engraved bookplates, and often signed them.

However, the bookplate wasn’t for Jefferson. During his lifetime, books were hand-printed and bound in small sections called signatures, and then those signatures were stitched together into the book. To ensure those signatures were put in the right order, each one had a tiny letter stamped on the bottom of the first page. “A” for the first signature, “B” for the second signature, “C”, etc.

In his books, Jefferson cleverly hand wrote a “T” before the small imprinted “J” and sometimes a “J” after the “T.” Nothing more. I can just see it. Jefferson, sitting alone in his study, tongue in the corner of his mouth, inking in a small “T” or “J” and nothing more. Smirking. It makes him seem mischievous and not just a little cunning.

Do you write in, or mark up your books as your own? How?

The bookplate of George Washington and others can be seen at Bookplate.org.

Learn more about Jefferson’s collection on display now at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC.