They walked through ancient empires, scaled snowy mountains, and defied societal norms, yet countless women from history remain silent, their stories lost in the shadows of their male counterparts. As I work on documenting the life of Eliza House Trist, I recognize that we writers have the power to resurrect these voices. Fully crafting female historical characters, we can allow them to resonate with readers of all ages, and also illuminate the richness and complexity of the past.

But how do we create these women who leap off the page and touch hearts across generations? Here are three key ingredients:

1. Unveiling the Human Beneath the History

While historical context paints the backdrop, don’t let dates and events overshadow your character’s inner world. Dive into their hopes, fears, vulnerabilities, and passions. Make them laugh, cry, yearn, and rage. Readers connect with characters who feel real, whose triumphs and stumbles mirror our own.

2. Challenging Norms of Female Historical Characters

Don’t shy away from portraying the limitations women faced in their era. Whether it’s societal expectations, legal restrictions, or even the physical realities of life, these constraints often fueled unique forms of resilience, resourcefulness, and rebellion. Show how your character navigates these obstacles, revealing both the external struggle and the internal growth it sparks.

3. Finding the Universal in the Specific

While historical details bring authenticity, the core of your character’s journey should resonate with readers beyond their time period. Is it a fight for justice, a yearning for love, or the quest for self-discovery? Grounding your historical narrative in timeless themes ensures your characters speak to readers across generations, sparking empathy and understanding.

Examples of Writing Female Historical Characters

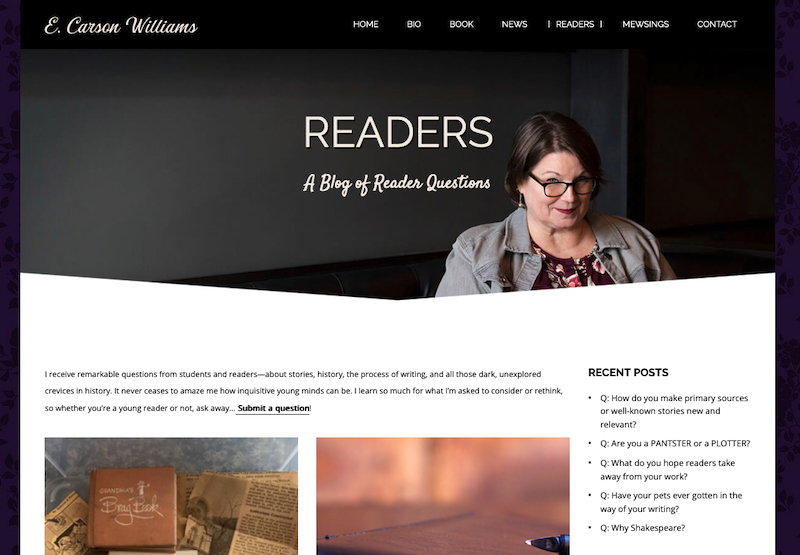

For further inspiration, dive into the works of authors like E. Carson Williams (Lis), whose newsletters celebrate the bravery of lesser-known women who are deeply inspiring to young girls today. (Her answers to reader questions are worth readings and the Mewsings from her cats are also hilarious.) Or author Linda Sittig, whose books and blog—StrongWomeninHistory.com—illuminate the lives of female pioneers and history-makers.

For an example of how to make history also wildly entertaining, immerse yourself in podcasts like The History Chicks. Bethany and Mini uncover the extraordinary stories of women hidden in the annals of history, like Mexico’s La Malinche. Don’t have time for a 90-minute podcast? You can check out their minicasts and each podcast begins with a 30-second summary.

Need some practical resources? Check out my own guide on researching women like a historical novelist to help you write beyond the genealogy of a figure. By learning more about their networks and connections, you can weave them into narratives that captivate, educate, and feel more like our own lives.

By bringing female historical characters to life, we not only honor their legacies but also expand our understanding of the past and present. So, pick up your pen, tap your keys, and let the forgotten women sing their stories – the world needs to hear their voices.

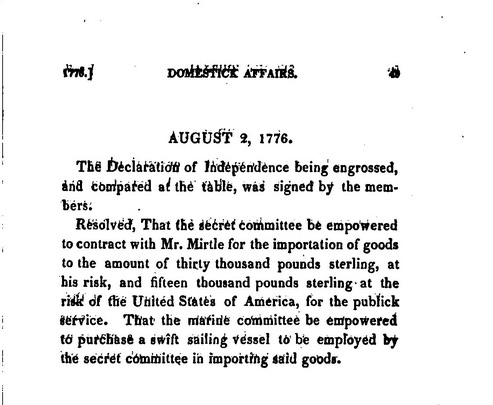

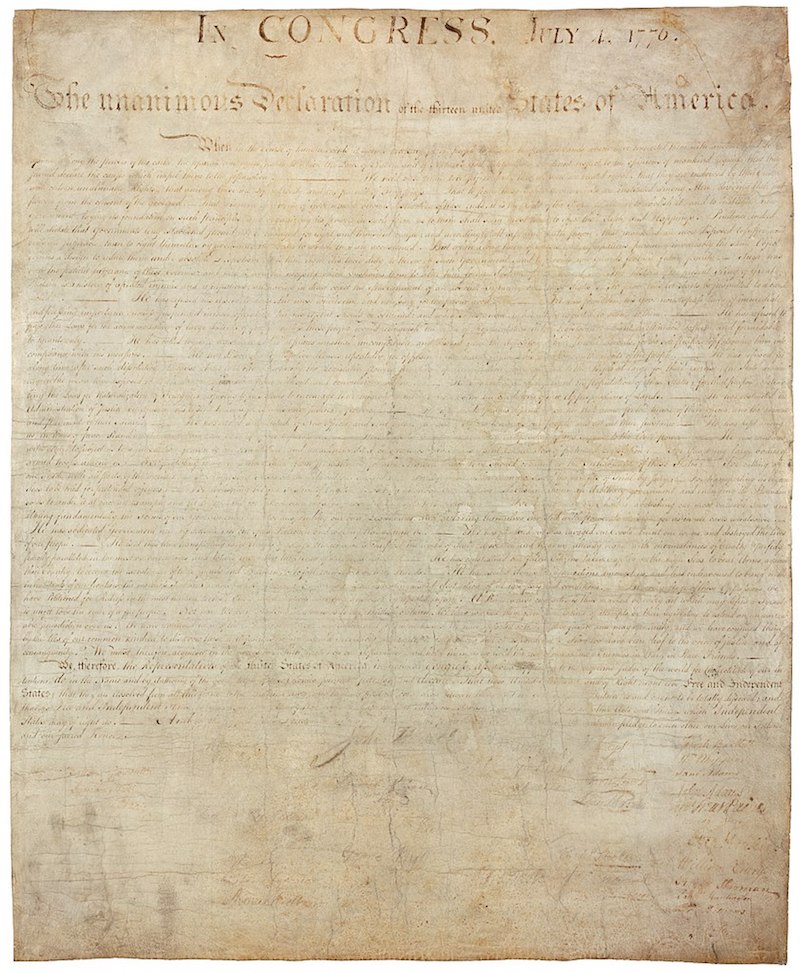

The Sole Declaration of Independence

The Sole Declaration of Independence