In late November, I had the good fortune of touring Bartram’s Gardens in Philadelphia, PA—a 50-acre garden in existence since 1728. The oldest surviving botanic garden in the US, the sloping and tiered lands on the western banks of the Schuylkill River were home to John Bartram—a botanist, collector, and explorer—and his son, William Bartram. Their garden was a source for seeds and plants for many of America’s founders including Washington, Jefferson, and Madison. My tour was for research for my next historical novel, and specifically to learn what those gardens looked like in 1787 when James Madison and others visited the gardens during the Constitutional Convention .

Why tour historic gardens in winter?

Now, before you go believing I’m nuts for touring a garden during winter (rather than July when Madison visited) such off-season tours mean fewer tourists and an occasional late bloom/fall burst of color. In our case, the oldest Ginkgo tree in America and the Tea-Oil Camillia, were giving a brilliant show.

The best reason has to do with wandering with a guide. Because there is less to do in winter, the curator—Joel T. Fry, who has been with the gardens since the late 90s—seemed to have all the time in the world to help me prune away the gardens as they are “now” in order to visualize them as William Bartram did “then.”

Bartram’s Gardens then and now

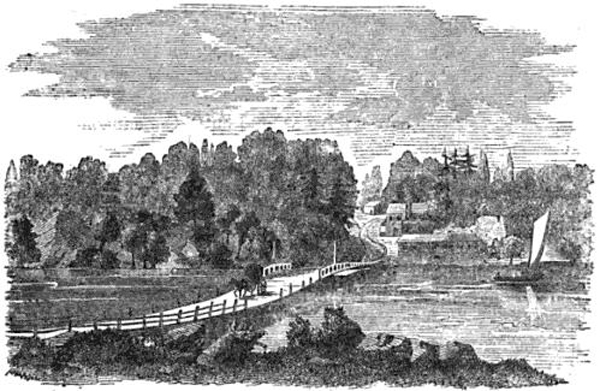

When the British moved through Philadelphia during the Revolution, troops built a floating bridge across the Schuylkill River east of town. What had been a ferry system from Grey’s Landing just few miles from Independence Hall, became a series of floating planks permitting visitors to land just a tad north of Bartram’s.

I wish I could say the view shown in this historic 1838 drawing () was equal to the view now. Today, one approaches Bartram’s via a graffiti-strewn bridge, and enters from the less-attractive back lane.

Back in 1787, however, a visitor would have first seen the tiered beds of plants—collected from various states as far south as Florida—rising up to the main house (like the photo above). Greens, tubers, and other edibles would have been planted closest to the house in the kitchen gardens. Built by John Bartram, the house was added onto many times, but the architecturally arresting structure remains.

The numerous trees scattering the property now would likely have been in a specific grove to one side of the house. That Ginkgo tree? In 1787, it was just two years old, so likely shorter than me, and in a different location. It now towers more than two stories tall. You can see an original William Bartram illustration of the garden map, on the Bartram Garden’s website here.

An incomplete archive of plantings

What was planted where and when by William, however, is difficult to ascertain. Although Bartram’s sold seeds and plants, “we don’t really have garden records from that time,” Joel shrugged as we chewed on some of the spinach miraculously still growing and plump despite a few frosts. “We don’t know if the records were thrown out when the family later lost the property, or if perhaps the Bartrams weren’t that good at keeping records in the first place.”

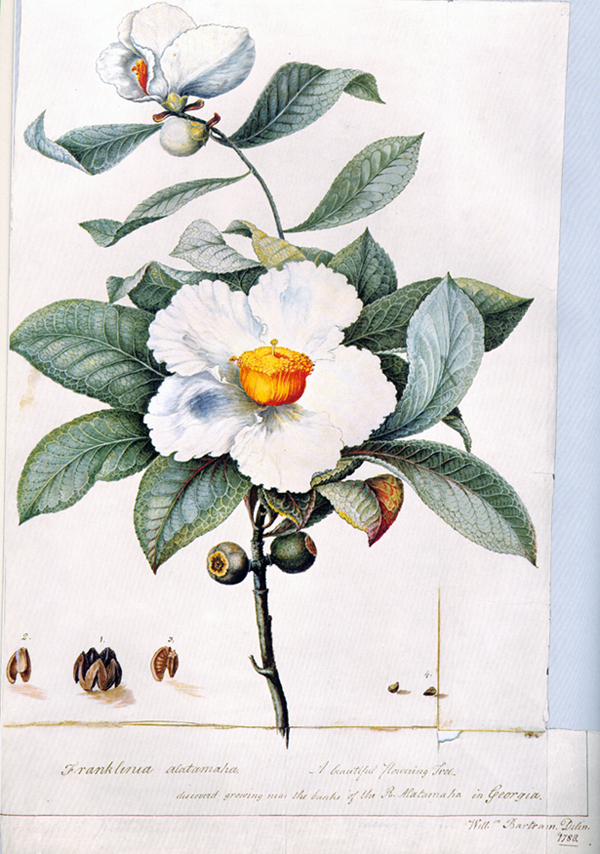

Personally, I find the latter easy to believe. John and William both seemed so enchanted by illustrating, collecting, exploring, and experimenting with plants and seeds, I can see them failing to write it all down at the end of a day’s digging. Their minds were likely their libraries and journals. Although Williams botanical illustrations are in some ways a series of singular plant records, like his study of Franklinia—a tree named for Franklin, and the garden’s signature tree.

Visitors post-Revolution might also have seen a working cider mill along the banks. Again, the Bartrams papers have no record of it, although a reference to it appears in a letter from a visitor named Manasseh Cutler of Massachusetts. “[Bartram’s] cider-press is singular; the channel for the stone wheel to run in for grinding the apples is cut out of a solid rock; the bottom of the press is a solid rock, and has a square channel to carry off the juice, from which it is received into a stone reservoir or vat.”

What Captivated Me Most in Bartram’s Garden

“What we’re doing is what William loved to do with visitors in the garden.” About half way through our tour—many stories in, the wind picking up, and much history shared—Joel smiled as he gazed across Bartram’s garden glittering with fall leaves. “We’re walking the paths and sharing ideas about the plants and other events of the time. It’s a chance to learn together.”

Nothing warmed my heart more on that cold November day. Thanks to Joel, in my next novel I expect you’ll find my protagonist Henry (along with other characters real and fictional) sharing ideas while wandering those same paths with William.

I urge you to visit Bartram’s Garden, and not just at the height of spring or summer, so hopefully you will be captured by this historic place, too. Just a 15-minute drive from Philadelphia, it’s a 50-acre respite for the city-weary soul Chasing Histories.