During this Women’s History Month, and ahead of the nation’s 250th celebrations, I have the great fortune of announcing a new Revolutionary female Patriot. I spearheaded an application with the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) to prove a new female American Revolutionary-era Patriot.

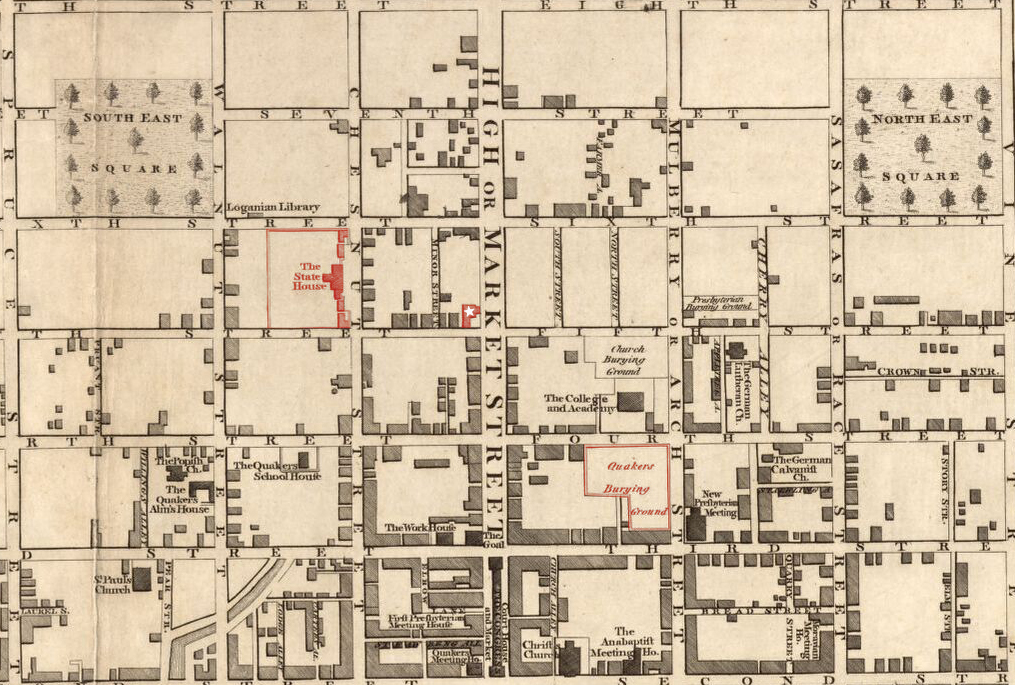

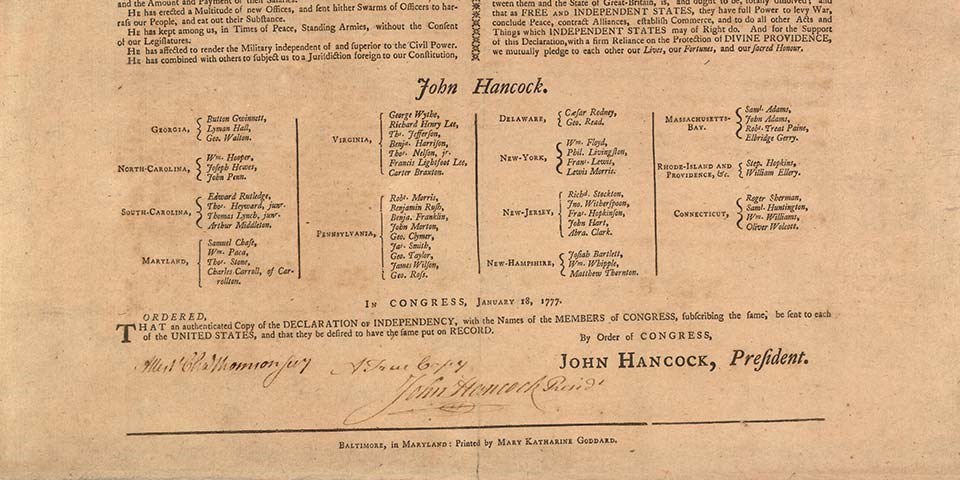

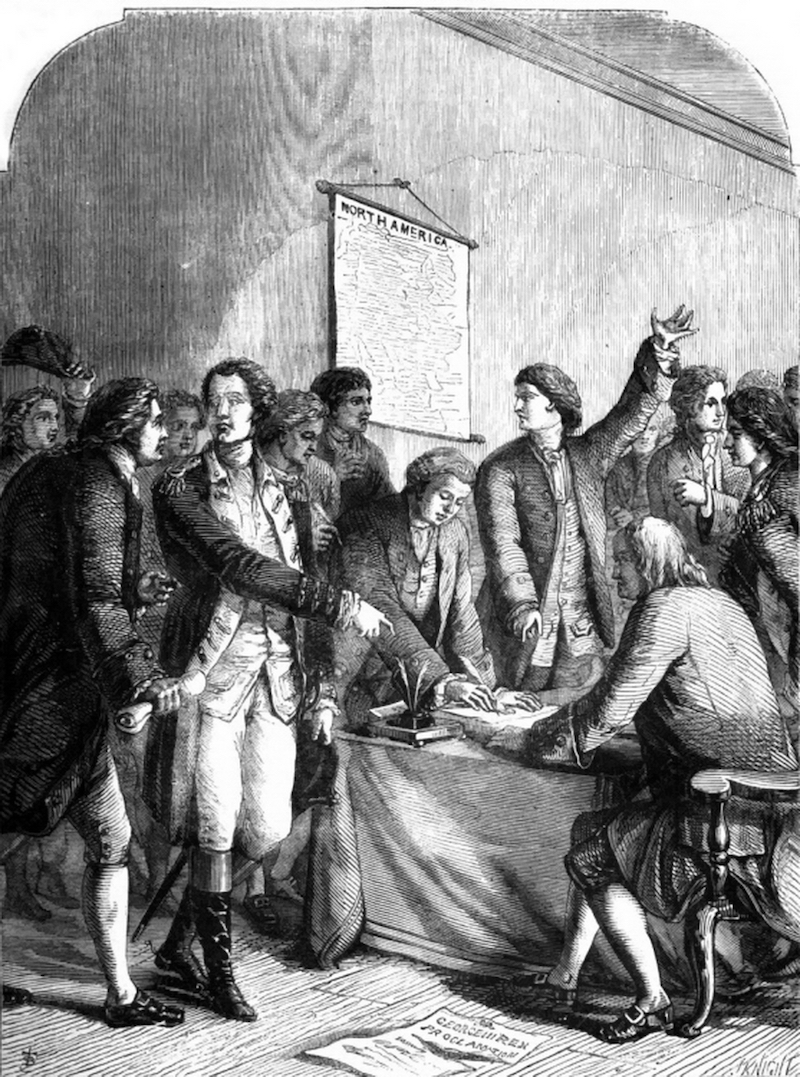

Mary House owned and operated a boarding house in Philadelphia, the House Inn. Because she paid taxes on the inn, her support tax directly helped fund the Revolutionary war. Just two blocks from the famous State House, where Revolution was debated and the Declaration of Independence signed, the inn was a respected political hub, frequented by familiar founding fathers.

In this press release issued by NSDAR, Pamela Wright, NSDAR President General and the National Society’s volunteer elected CEO, says, “We are thrilled to add Mary House to our list of verified female Patriots. As we approach our nation’s 250th birthday, DAR members across the country are concentrating on sharing the stories of these amazing Americans, helping contemporary U.S. citizens understand the relevancy of Patriots to our lives today. As a female entrepreneur myself, I am inspired by the story of Mrs. House.”

The House Inn hosted Thomas Jefferson and Other Founders

Mary House was a wise entrepreneur. After her husband died, the widow established the boarding house, which quickly became known for what was then called “fine entertainments.” It offered quality lodgings, good food and refreshments, and above all an atmosphere that encouraged convivial engagement. It quickly attracted founding fathers familiar to us now. Silas Deane, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson. Mary recognized that congressmen visits to Philadelphia would increase as Revolution rumbled through the colonies. Consequently, she wisely moved her already established House Inn closer to the action, to Fifth and Market Streets. Like the famed City Tavern, the House Inn was a gathering place for end-of-day political discourse over dinner and drinks.

Finding Mary House and Proving Her as Patriot

Although I spearheaded the search and the NSDAR application, the journey to validate Mary House’s Patriot status was a collaborative effort. It took multiple years and involved more than 15 individuals across five NSDAR chapters and three states, along with additional historians and translators. To submit an application for patriot status for Mary House, we found and proved lineage to a living descendant. That descendant is also related to two other significant figures: Jefferson and the subject of what I call my Eliza Project.

Mary House’s Daughter, Eliza Trist, Went West & Kept a Journal

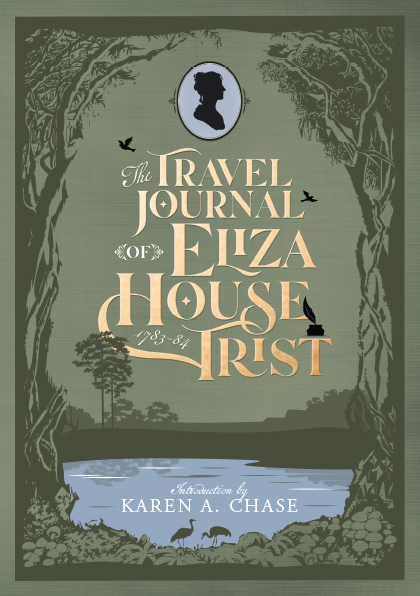

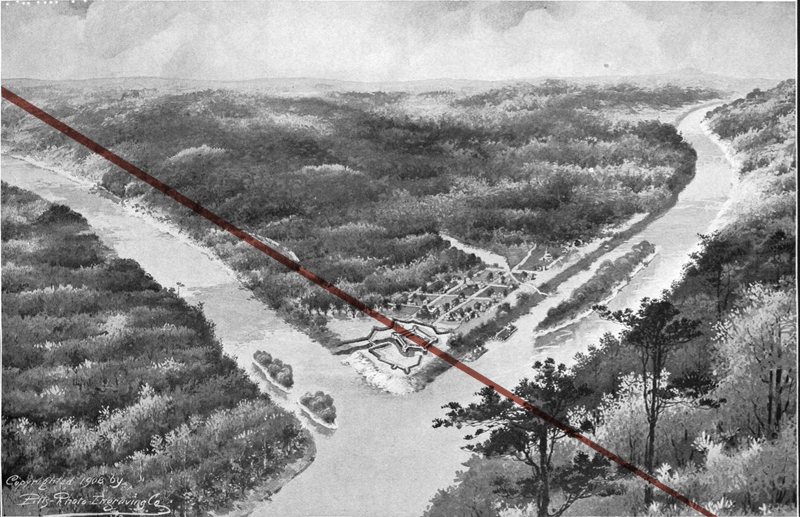

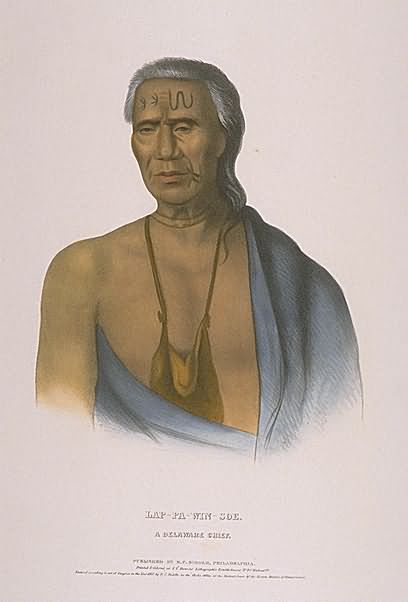

Mary House is significant in her own right as a supporter of the Cause and an entrepreneur. She is also the mother of Eliza House Trist—a woman who traveled west in 1783, two decades before Lewis and Clark. Eliza Trist kept this journal for Thomas Jefferson. Trist met Jefferson when he lodged at the House Inn. The two became significant in each others lives, and long after her westward journey, Eliza Trist’s grandson married Thomas Jefferson’s granddaughter. Consequently, this new NSDAR member on this application, is related to House, Trist, and Jefferson.

To be frank, I feel like we’ve hit the NSDAR’s version of a quadfecta or superfecta. Myself, and this incredible network of genealogists and historians, have correctly proven four positions significant to the NSDAR. New female Patriot. New Female Explorer. New member. And all connected to Thomas Jefferson.

What will the Patriot Status Achieve?

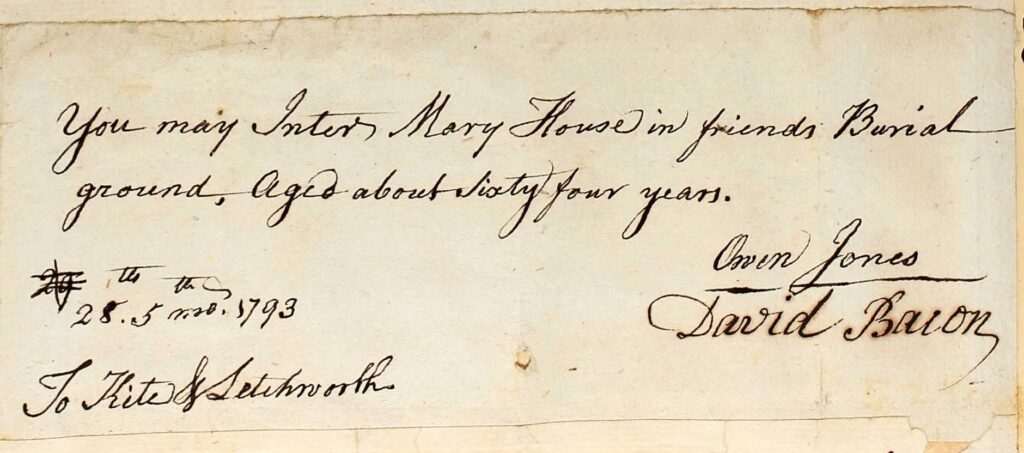

Mary House was buried in Philadelphia, in the Quaker Arch Street burial ground, which was built over in the late 1800s. Eliza Trist is buried at Monticello. Neither woman has a gravestone, and their contributions have never been granted state historical markers. As I mentioned in the press release, “The goal is to ensure each of these women has a grave marker and historical recognition… In honor of the 250th, we are striving to broaden the narrative we tell about the founding of this country. Eliza and Mary matter. Who we tell our origin stories about matters so more of us can envision ourselves contributing to our future.”

To learn more about Eliza House Trist

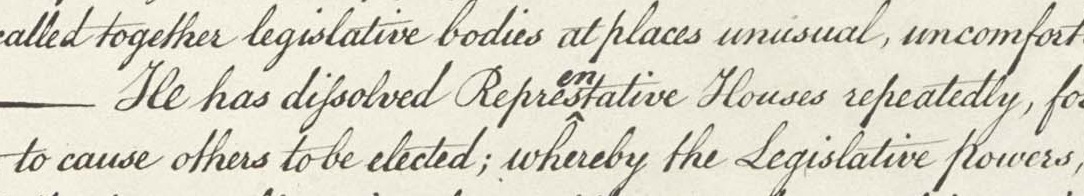

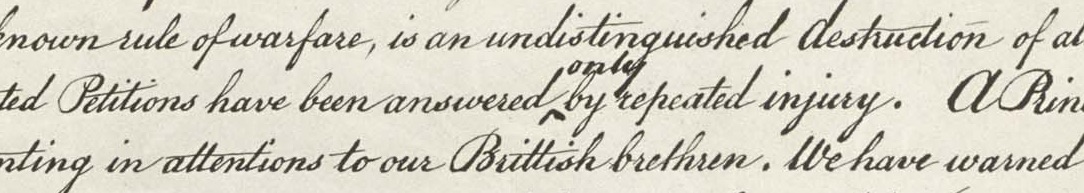

I am producing a more comprehensive and widely-accessible narrative for Mary House and Eliza Trist. For now, you can learn more about Eliza House Trist’s journey when you pre-order a copy of The Travel Journal of Eliza House Trist, 1783-84. It’s a brand new transcription, with a brief introduction. For the first time, her journal is replicated as she originally wrote it. In this beautifully hardbound book, is an all new introduction and a map of her journey. The book publishes April 15th.

McKean wrote to John Adams about being, “hunted like a fox by the enemy, compelled to remove my family five times in three months, and at last fixed them in a little log-house on the banks of the Susquehanna.” No small feet with five children and his second wife pregnant with number six.

McKean wrote to John Adams about being, “hunted like a fox by the enemy, compelled to remove my family five times in three months, and at last fixed them in a little log-house on the banks of the Susquehanna.” No small feet with five children and his second wife pregnant with number six.

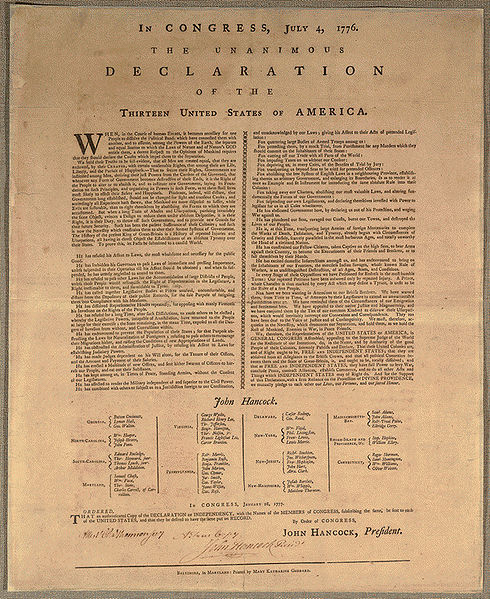

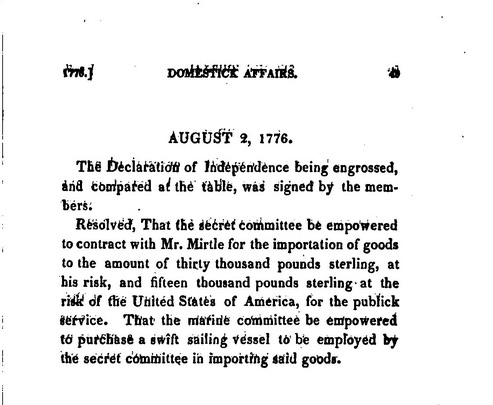

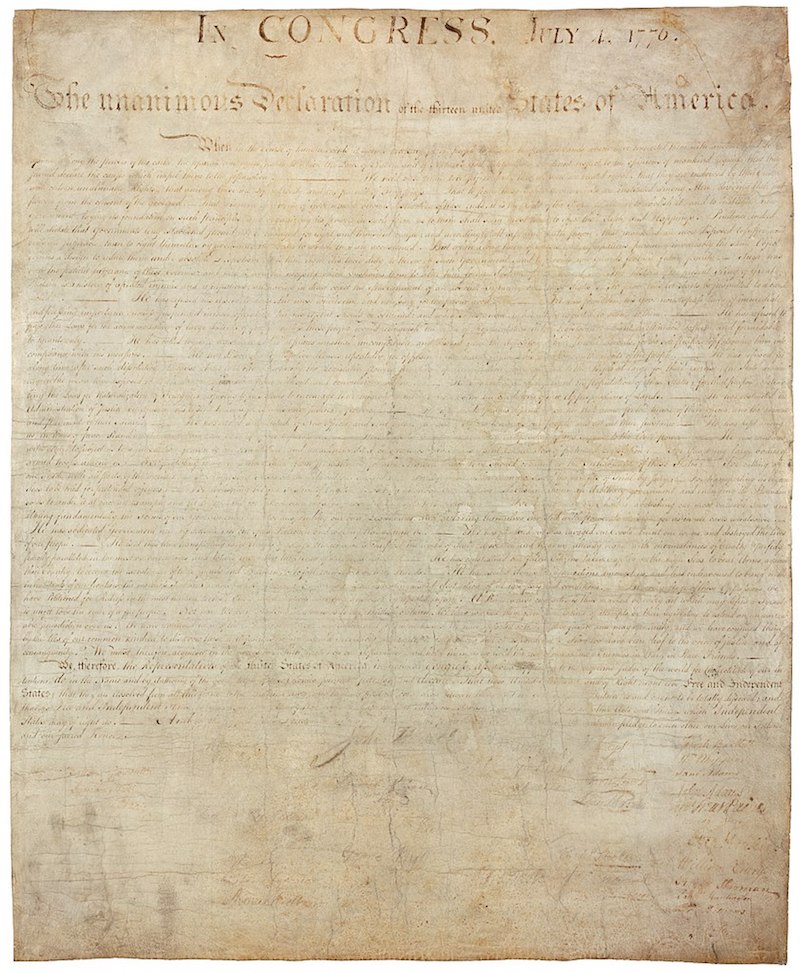

The Sole Declaration of Independence

The Sole Declaration of Independence

After much thought, and in the spirit of the document, I am limiting the number of signed copies of my novel to just 76 (in honor of the year 1776, of course). I am reserving the first 20 copies for personal use and charitable endeavors, and 56 are being made available on a first-come-basis to the public during the pre-sale period, which begins this Thursday on April 11th. Each of those 76 copies will have a full signature, each will be numbered, and each will carry my personal seal (shown here).

After much thought, and in the spirit of the document, I am limiting the number of signed copies of my novel to just 76 (in honor of the year 1776, of course). I am reserving the first 20 copies for personal use and charitable endeavors, and 56 are being made available on a first-come-basis to the public during the pre-sale period, which begins this Thursday on April 11th. Each of those 76 copies will have a full signature, each will be numbered, and each will carry my personal seal (shown here).