Founding-Documents Blog Series: Part Six

On this, July 4th, my blog features the last in a brief series related to the history and signing of the Declaration of Independence… Part one began here.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

So many blogs will rightly tell you that the Declaration of Independence was not written, voted for, or even signed on July 4th. All true. Today, however, I’d rather talk about the only woman whose name graces the Declaration. A woman featured in Carrying Independence.

Mary Katharine Goddard

Her brother was a drunkard. He owned his own print-shop which often fell into neglect as he stumbled around the colonies bemoaning (whining) that Benjamin Franklin had been given the title of Postmaster General over him.

When the print shop was left in Mary Katharine’s hands in Baltimore in the mid 1770s, Mary Katharine (with two As) became known not only as the printer, but the editor and the first female Postmaster of Baltimore. (As she says in novel, “It does not take a man to organize the mail… I was already writing and publishing both the Maryland Journal and the Baltimore Advertiser, so why not know the post routes, too?”)

Postmasters in the colonies were paid by Congress, making Mary Katharine the first female federal employee of the newly formed United States. But by the end of 1776, problems in that new country were afoot.

Congress Had a Failing Army

Getting all the congressmen to sign a sole copy of a Declaration—while hiding their identities—was one thing. Ensuring troops stayed to fight was quite another. By January of 1777, the enlistments of soldiers who had joined in July of ’76 were nearly up. Their morale was severely down. Would you have stuck around after 6–8 months of marching, starving, and losing, or would you go home to tend your farm and eat?

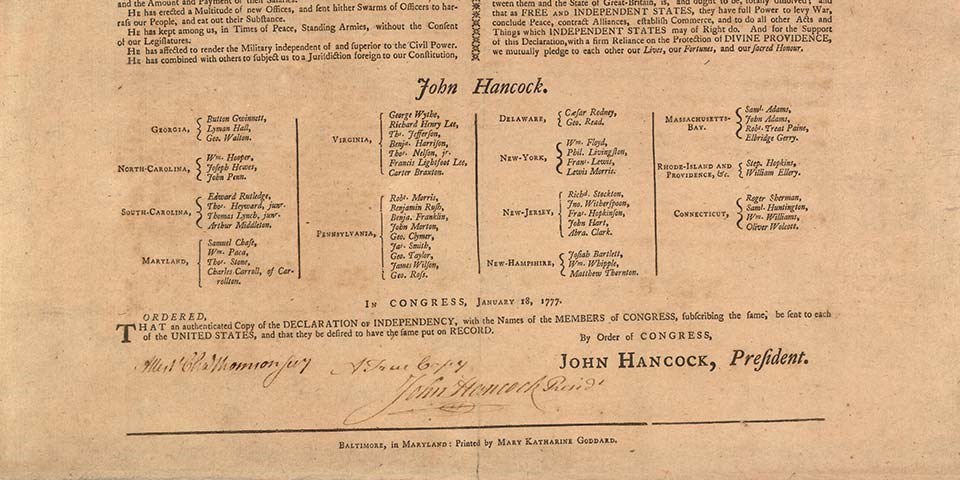

Congress decided to admit “to a candid world” who the signers were. They put out the call to printers asking them to make a copy of the Declaration with all their names typeset so all those soldiers could see exactly who and what they were fighting for.

A Woman Volunteers

Enter Mary Katharine Goddard. In February of 1777, she volunteered her print shop in Baltimore to print documents, called broadsides. She used the font Caslon, which, ironically, was created in a type foundry in England. Two hundred copies were made and circulated among the states. To date, nine copies still exist.

Only one signer’s name does not appear on the Goddard broadside. That of Thomas McKean of Delaware. It’s believed that when Goddard printed these copies, the congressmen had yet to sign the original—further proof that the congressmen were not all together on August 2nd for the formal engrossing.

Although her name doesn’t appear on the original signed version of the Declaration, I still point to her when historians ignore women’s roles in the struggle for independence. Mary Katharine not only participated, she even had the wherewithal to typeset her own name on her copies, thereby inking herself into history.

The Smithsonian has a lovely article by Erick Trickey on Mary Katharine Goddard‘s life, background, and achievements.

Reader Insider Note: In order to make copies like the Goddard broadside, printers often worked alongside the original document. In my novel, my protagonist, Nathaniel, not only delivers the document, but stays to help Mary Katharine Goddard typeset the thing. To read how it was done, and to see the sparks fly between Postmistress and Post rider, you can get the book… (ahem—it’s just 99¢ all this week).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

For more history nerd posts like these, subscribe to the blog. Guest posts are welcomed and encouraged. Contact me for details.

For behind-the-scenes author-related news, giveaways, and to find out where I might be speaking near you, subscribe to my e-publication, CHASING HISTORIES.