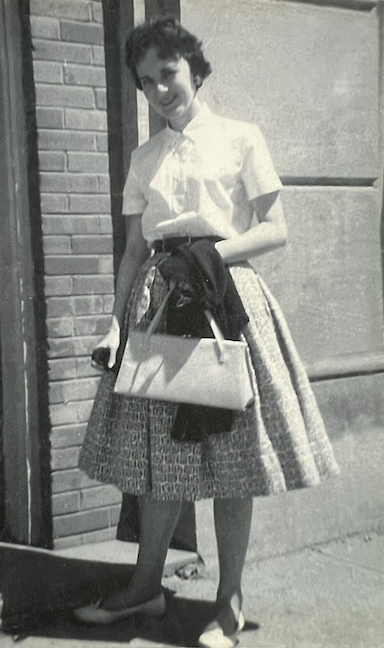

On April 3rd, we lost my mum. Margaret Lindsay (Klock) Chase. Wife. Mother. Aunt. Friend. My family and I appreciate everyone who has commented about their experiences with her or shared their condolences. Here is our tribute for her, along with some of our favorite images. We’re sure they will make you smile. You may want to grab a tissue… We’ve certainly gone through our fair share.

Margaret Chase: 1940 – 2024

She was just so sweet. This phrase has been the one most spoken this week about Margaret Lindsay (Klock) Chase, age 84, after her passing on Wednesday, April 3, 2024, in Medicine Hat, Alberta. She was a girl from Saskatchewan. Simple in needs and wants. One might even say she was ordinary. And yet, for those who never met Margaret, you’ll soon understand why it’s a shame you did not know this extraordinary person.

The Early Years

Life, for Margaret, began Naicam, Saskatchewan on March 26, 1940. A town with a population of just 267—it’s only 670 or so now. She was born to Margaret Catherine (Floss) Klock, who had come to Canada from Chicago, and Erie Klock, who farmed land he’d acquired through the Canadian Homestead Act of the 1930s. The third and accidental child, Margaret was just two months old when her father died of Leukemia.

Suddenly, what might have been a harvest life, was now hardscrabble. Aside from affection from a stray cat named Toby, she and two siblings (Catherine and Frank) endured crushing winters and windy prairie summers. Home was troubled by a grieving and often difficult mother. Margaret recalled an embarrassingly dirty house, albeit one also littered with books. She was always thankful for the gift of reading, but also recalled a year she was thankful for shoes. They’d been given to her by a friend who had outgrown a pair. Those hand-me-downs saved her from being among a handful of students who went to the one room schoolhouse barefoot.

Through such gifts in her tiny post-depression town, she learned gratefulness. That trait helped her make friends—like Donna (Brodt) Fleming—who enabled her to make the most of her growing up years. With them, she played hockey. Learned to figure skate. Joined the basketball team. Truly non-denominational, she often accompanied her friends to their respective churches on weekends—relishing in the shared meals and a joy of music that would only grow and deepen over time.

Soon after high school, she headed to the big city of Moosejaw, Saskatchewan to find work.

“I remember staring up at the tall buildings with my mouth hanging open,” she once told her daughter, Karen. “And those buildings were just three or four floors. It was silly to think they were big after seeing Chicago and New York years later.”

In Moosejaw, she began working for the Saskatchewan Power Corporation in 1960, as a clerk for engineers. With only two skirts, and a couple tops to wear, she worried she wasn’t looking smart enough for such a job. She recalled her boss pish-poshing it as nonsense. She was just what they needed. Presentable, clean, and always willing to work and lend a hand to others.

It was that smart simplicity that she exuded when Cecil Chase of Limerick, Saskatchewan strolled into the office. In his RCAF uniform, he came to pick up a friend—Margaret’s coworker and friend, Mabel—who needed a ride. That first look is all it took. After a little colluding with Mabel, soon they were on their first date to a baseball game. They were engaged a year later, and Margaret and Cecil married on June 23rd, 1962.

She continued to work with the Power Corporation in Regina as Cecil went back to school, and by the late 1960s, they’d moved to the even bigger city of Calgary, Alberta. Following a teaching opportunity at SAIT for Cecil, the move enabled Margaret to finally realize the career she’d deeply craved. Motherhood.

Years later, when women were said to have it all, she was asked about why she stayed home. “Let me make it clear,” she said, “I could have worked, and I chose motherhood. I can’t say everyone did, but I really chose it. And I loved it—every moment of it.”

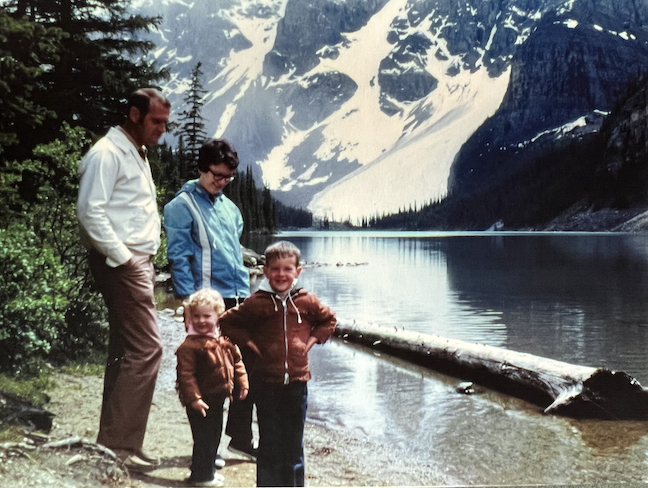

A son, Raymond Bruce, came first in 1968—just before the move to Calgary, and a year before man landed on the moon. Three years later, in 1971, a girl, Karen Alison, was the last to join the small family. Shortly before that, Margaret and Cecil bought their first home in Calgary, in Highwood, a relatively new neighborhood north of downtown. It would be their home for the next 18 years.

There on Hendon Drive, Margaret was industrious, a partner any working woman today would love to have by their side. She made every penny of Cecil’s teaching income go further by contributing on the home front, despite having no experience. At first she couldn’t cook a thing—her first attempt at biscuits would be forever called bullets. Enter Cecil’s mother, Effe (Marples) Chase, an affectionate mother-in-law who lovingly taught Margaret to bake and cook.

From then on, Margaret made every loaf of bread the family ate for 16 years. She pickled. Made jam. Filled three boxes with handwritten recipes. Planted a garden and raspberry bushes. Learned to oil-paint and make Belgian chocolates. Sewed Halloween costumes. Worked out to Jane Fonda. And created a tidy, warm house so welcoming, as one relative commented, “anybody could drop in, sit at the table, and right away feel at home.”

“She just handled everything that needed to be done,” Cecil said. “Things I hadn’t thought about—from birthday cards to homework to cutting coupons to painting the window trim. If it was needed to make our home and family life run efficiently and economically, she did it effortlessly. She made us work. Even when we started camping and traveling.”

On the Road and Meeting Others

By 1978, the Calgary house became what some people now call “Sticks-n-Bricks.” It’s the house you live in when you’re not traveling in an RV. Margaret and Cecil were determined to show their kids more than just the prairies of Canada. That year, they took the first of what would become an every-summer excursion via motorhome to see North America.

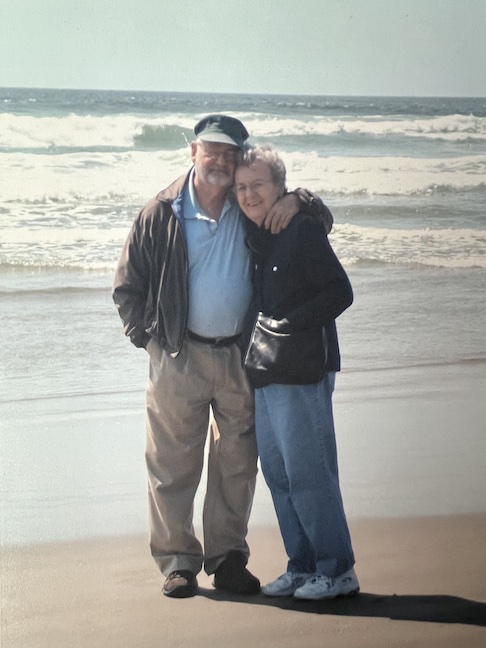

The trip was planned in part by Margaret to visit relatives she’d never met before. Paul Chaffee in Kansas City, and in Chicago a half-brother to her own mother named Charles Blanchard. In between were tours of historic places. Custer’s Last Stand. The Lincoln Memorial in D.C. And it was the first time, at 38 years old, that Margaret visited and fell in love with the ocean at Rehoboth Beach.

It’s thanks to Margaret, and her insistence upon keeping a journal, that the joyful experiences of that ten week trip and others were documented. She also tracked every dollar spent on camping, groceries, books, and gas. It amounted to around just $2600—coming in just under the money budgeted from what Cecil had earned teaching night-classes.

“Whether we were on one of those trips or at home,” her son, Bruce, said, “Mom was that person who kept track of details. And she never met a stranger. She’d pop into a grocery store to get a couple things, and leave us sitting in the car for half an hour because she’d ask someone about their day and really wanted to know the answer.”

Sister-in-law, Telva Chase, said , “Sometimes she’d be so busy asking about you, that the conversation would be nearing the end and you’d realize you hadn’t asked her a darn thing.”

That curiosity about others, and Margaret’s love of travel flourished after Cecil retired. The two bought another RV, threw a few things in storage, and for five years lived the nomad/snowbird life. They summered in Alberta, golfed and toured in south Texas in winter, and dropped in on folks—often by surprise—as they traveled full-time in the age before cell phones. She visited Fort Klock at Fort Plains in New York, exploring roots of her father’s family.

She had longed to hear an Irishman say her name (Margaret has a different roll on the tongue over there). And in 2007, thanks a trip with Cecil hosted by her son and daughter-in-law, she finally did. She wanted to, and did, kiss the Blarney stone. She lifted a pint and, despite an in-grown toenail, she hoofed her way without complaint at a swift pace across the cities and country-sides of Ireland, England, and Scotland.

Despite not seeking a career, she did work some. It included being receptionist and human resources assistant at the School Board in downtown Calgary. In the eighties, she sold microwaves at Market Mall—a job that led to her saying “just zap it” when food required reheating. Much later, after retiring from RV life and settled in Medicine Hat, Alberta, she sold barbeques at the local Walmart. She eclipsed previous sales swiftly. There are surely a handful of folks in Medicine Hat staring at a grill they don’t remember buying. But they certainly remember that nice chatty lady who sold it to them.

Before she was 60, she was a dual citizen of Canada and the United States. She’d visited 47 of the United States and nine of the Canadian provinces. Always she drank coffee (and an occasional rum), and wanted bacon and eggs as often as possible, even for dinner. She shared many a meal with family, and with chosen family in Calgary and Medicine Hat.

She could wipe the floor with you in a game of cards. She laughed heartily at a great joke, her head back and showing off her molars, but she couldn’t tell a joke to save her soul. She often told the punchline first, and then laughed even harder after declaring, “Blasted, I said it wrong didn’t I? Damn.”

The Other Side of Life

Now, before you go thinking that Margaret’s life was one joyful day, year, and excursion after another, here comes the rest of the story. Margaret’s concern for folks also meant that she often put others ahead of her own needs. And once the purpose of motherhood ended, and menopause crept in, there also came knocking a family inheritance—a depression that plagued her mother, her siblings, and her for decades. And then came a diagnosis that stuck to her like a bad penny. Bipolar.

Symptoms were kept at bay by a few medications for a few years, but once the traveling ceased, the ups and downs increased. Over nearly 30 years, those wide-swinging emotions were regulated by a series of trips to psychiatrists, who ordered an ever-increasing concoction of medications. Some worked for a while. Some did not. Some may have contributed to cancer. And one or two contributed to an eventual failure of her kidneys. Not enough doctors encouraged cognitive behavioral or talk therapy.

She willingly shared that realization in recent years with her daughter’s new partner, Ted Petrocci, a psychotherapist. “As inquisitive and thoughtful as she was,” Ted said, “Margaret absolutely would have benefited from it. She would have discovered solutions that would have eliminated so many medications.”

A saving grace for Margaret, was Cecil. He was a loyal and loving sounding board—always eager to help her get better, and to be the rock she clung to. She was grateful he loved her in spite of the issues and illnesses, and told him as much. Through it all, they upheld those vows they’d made 60 years earlier. Through good times and the darkest days, they always kissed each other goodnight. In the last months, they could be found together napping—one in a bed, one in a chair, still holding hands. And when her tired body was finally giving out, surrounded by the love of family and friends, it was to him Margaret looked one last time. On April third, she opened one eye, and held Cecil’s gaze until she left the world.

Would she have wanted anyone to write about how challenging her last three decades and that horrible diagnosis were? No, probably not. She often asked not to let anyone know she suffered from depression and illnesses, and many probably had no idea. The smile was often a mask. And for those old friends who wondered why she stopped calling, many never knew it was because her mind was often too heavy for her hand to pick up the phone. So why share such private details now when we’re celebrating her life?

Why Margaret Matters to Us All

When we write obituaries, we often share useless dates. When we read famous obituaries or hear eulogies, we want to know what the person accomplished. What did they contribute to mankind? The reality is, most of us are trying to just live. And for so many, life doesn’t afford space for grand achievements. At best, it’s ordinary. Simple. But it can also be complicated. Difficult or dark. It’s not always sunny even when the sun is out. And yet…

Margaret is an example of how mental and physical health can either derail a person, or we can choose to spread joy in spite of the hand we’re dealt. No matter how simple or difficult our lives, it’s really our little acts of kindness for others that bring more sunshine than rain.

No matter how much her diagnoses and medications and surgeries impacted her health, she had a smile to share, and her heart was always declared to be strong. Caregivers and younger people quickly called her Mum. She hugged unconditionally. Everyone, no matter their stature or job or race or gender, had a story, and she wanted to know it.

To her, everyone mattered. And therefore, so does she.

Let’s Be More Margaret

In a world troubled by divisiveness, war, and unrest, we all might try to be a little more like Margaret Chase. How?

- Maybe it’s sharing a bright smile like hers.

- Maybe you stop in the grocery store to ask a stranger how they are, and it’s such a genuine ask, you both talk next to the tomatoes for half an hour.

- Maybe it’s not what you wear, or how many things you own, but that you pitch in to help when needed, and without being asked.

- Maybe you make memories by saving your pennies to travel, by sharing shoes, or by simply singing with or to someone.

- Plant a garden or at least white daisies (her favorite).

- Certainly, it’s gathering around the table with friends and family, and laughing even when you feel like crying.

- Be sure you kiss someone goodnight.

- Show gratitude and tell them you love them, no matter how hard the day.

And then, as she has, you’ll make it incredibly damn difficult for friends and family to think of a world without you in it. Fare thee well, sweet Margaret. We lift a pint to you and happily say we are all so very glad you were here.