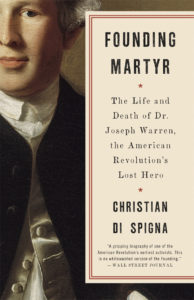

It’s been six years since Carrying Independence, my novel about the Declaration of Independence, was published. Now, we are a year away from celebrating the 250th anniversary of that document on July 4, 2026. In honor of that anniversary, I feel compelled to share this story more widely—my gift to my fellow Americans.

Starting today, I’m releasing Carrying Independence, chapter by chapter—leading up to the 250th—on my new Substack Publication: From the Wandering Desk of Karen A. Chase.

Along with it, every other week on my blog here, I will take you on a deep dive about a historical fact within that week’s chapter. You can also join the conversation, and collectively we can have a good (and civil, please) discussion about our Declaration.

Why This Revolutionary War Novel Matters Now

This story matters, now more than ever, for two compelling reasons.

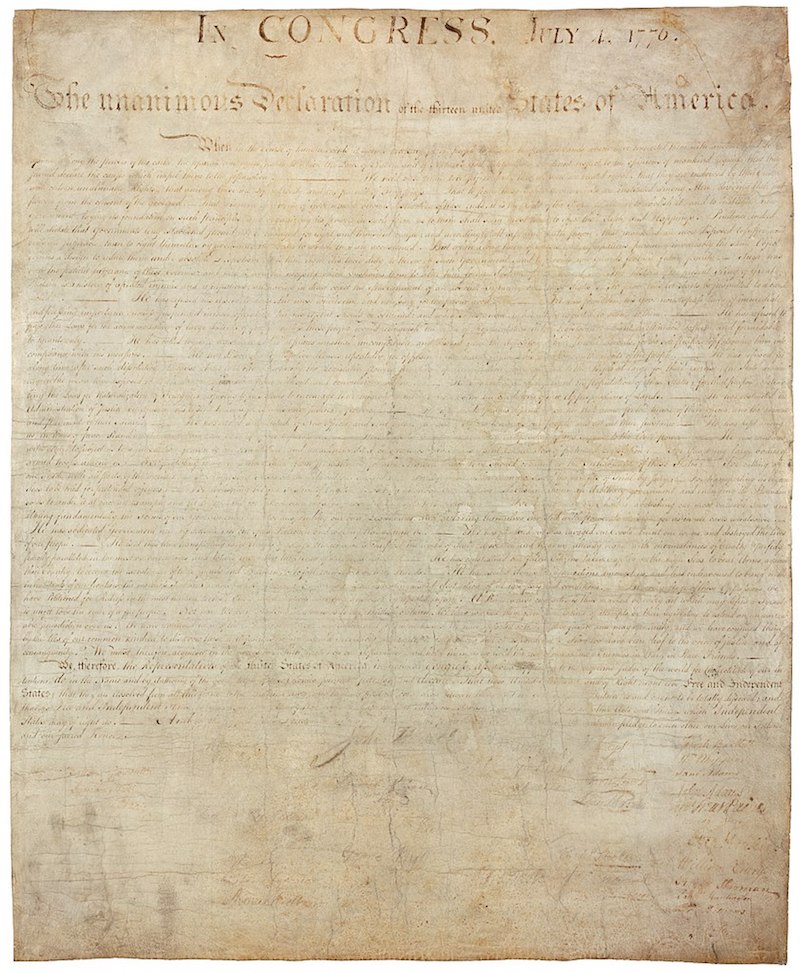

First, it’s a celebration. The 56 chapters I am releasing are a tribute to the 56 men who ultimately signed that one sole copy of the Declaration on August 2nd, 1776. In reality, however, in 1776, it was thousands of ordinary individuals—not merely those founding fathers—who decided to band together behind a Cause greater than themselves. And that action became the motto of the United States. E Pluribus Unum. Out of many, one.

Second, it’s necessary. Today, various news outlets and politicians use our founding document for sound bites and publicity, often describing its purpose or content incorrectly or without context. Such acts are dividing us at a time when we should be coming together, just as we did in the beginning. As Thomas Paine wrote in American Crisis, “The period is now arrived, in which either they or we must change our sentiments, or one or both must fall.”

The Untold Story of Our Declaration of Independence Founding Document

When I began researching this book in 2009, I discovered something remarkable: there were no historical novels focused on the actual process of signing the Declaration of Independence. Everyone knows the document, but few knew when it was formally signed (August 2, 1776). Even fewer knew how. (Historians still debate this point.)

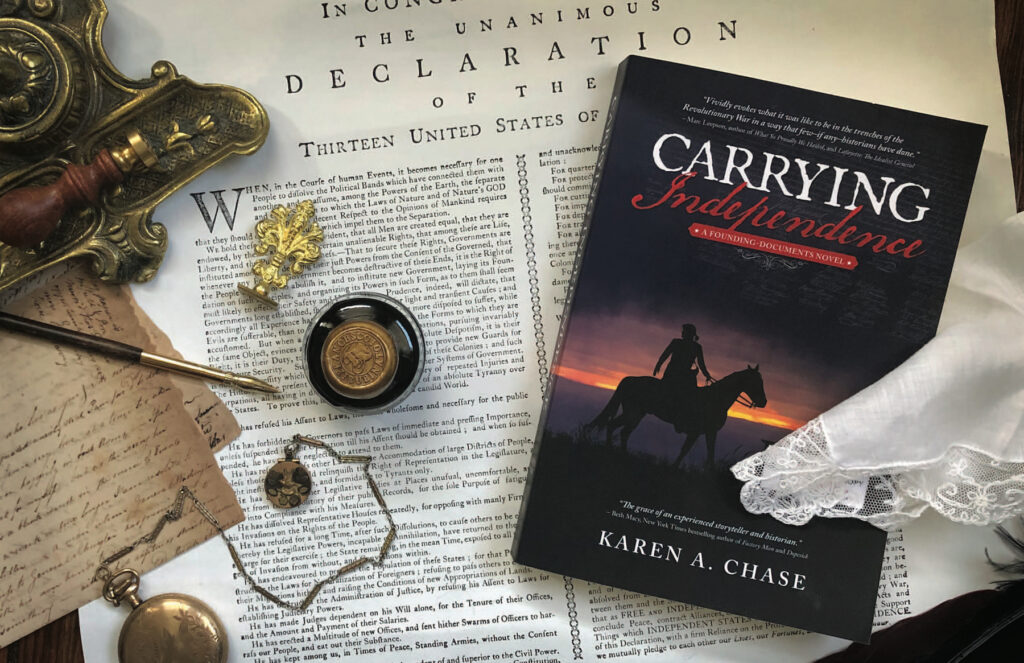

Carrying Independence tells the story of Nathaniel Marten—a reluctant Revolutionary War courier tasked by Congress with carrying the document (hence the title) and acquiring the final signatures on a sole copy—a contract that would unite us as one nation. The novel opens at a woodpile, with Nathaniel—the very man charged with the Declaration’s protection—determined to destroy it. Because all seemed lost. Because we were losing that war.

My Goals in Crafting This Historical Novel

Choosing to write a factually-accurate historical novel about a document everyone knows—yet of which I knew very little—seems, well… foolish. Yes, looking back, that’s the word that comes to mind. To set that Revolutionary War novel during a time period I also knew scant about? About a war so long ago that even the most deeply born-and-bred Americans have six or even eight generations between them and 1776? Ludicrous.

I don’t tend to do things halfway. (Hold my ale.) So, I set two ambitious requirements for this Revolutionary War story:

Share deeper, lesser-known truths. I wanted readers to repeatedly ask, “Was that true? How did I not know this?” By revealing true yet hidden stories about real people and events, I hoped to make even well-informed Americans question what they thought they knew about our founding. (Did you know a woman’s name is on a 1777 copy of the Declaration—the first to broadcast all the names?)

Create genuine suspense about known history. I needed to weave unknown facts with familiar events to generate such tension that even Revolutionary War enthusiasts would worry about the outcome—like watching Apollo 13 and wringing your hands over whether the crew actually made it home safely.

The Response Has Been Extraordinary

Did we win? Or did the Redcoats? Did the Declaration of Independence actually receive all the signatures? Or was it stuffed in a dresser somewhere, or worse, thrown onto a fire by the very person tasked with its completion?

Since publishing Carrying Independence in 2019, the response has been remarkable. Thousands of copies sold in the US, Canada and even the UK! Over 100 presentations and book clubs nationwide. (And now even a job as an onboard history lecturer on American Cruise Lines as a result!) A handful of awards, including second place in the Cinematic Screencraft Cinematic Book competition, and being recognized as Number 12 of the Top 100 Indie Books of 2019. An award for independence. How fitting.

I’m thrilled by readers who’ve shared how worried they were while reading. One woman told me she yelled out loud, “No, Nathaniel, don’t go in there! You have to finish this!”

I’m in awe of historians who asked me for resources I’d discovered so they could research more about these lesser-known Revolutionary figures and events.

And I’m honored by Americans linked by lineage to Patriots—Daughters and Sons of the American Revolution—who said they picked up the Declaration of Independence and read it beginning to end—some for the first time.

Why the Revolution Was About More Than Battlefields

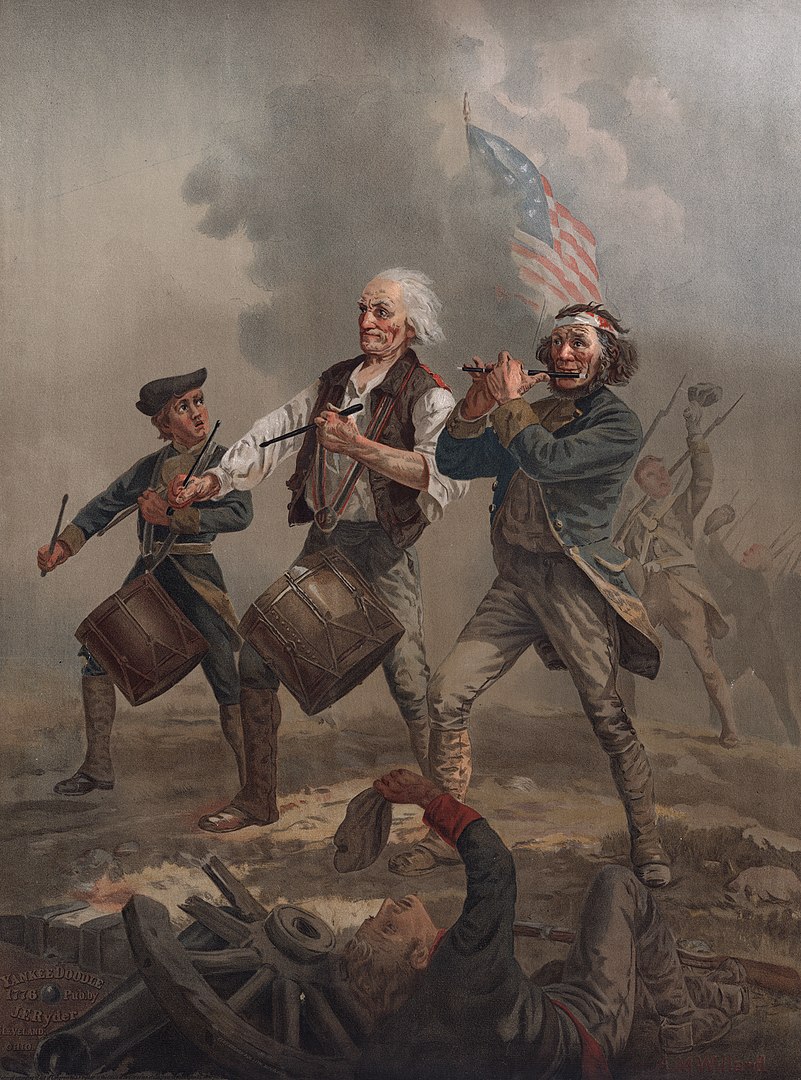

The Semiquincentennial celebrations of our founding document is the perfect moment for more of us to learn about the Declaration’s journey through a war that could have ended very differently. A war won against insurmountable odds, and fought, in part, for the ideal of becoming something better. However, unlike what we’re taught in school, the Revolution wasn’t just on battlefields. Hopefully, by reading Nathaniel’s story, you’ll understand why John Adams said the real American Revolution “was in the minds and hearts of the people.”

Join Nathaniel’s Journey to July 4th, 2026

Today, there is no other historical novel about the American Revolution quite like this—focused on the actual signing of the Declaration of Independence, following a reluctant courier through the perilous journey that brought our nation into being.

Although Nathaniel is fictional, you’ll discover the facts about how our founding document and this nation came into being against impossible odds, a Cause carried by ordinary people like you and me who chose something bigger than themselves.

This story isn’t just mine. It’s ours. At the very least, I hope you’ll learn about and read our original Declaration of Independence. As Nathaniel’s father says at a critical turn in the novel, “The only person more ignorant than a man who cannot read, is one who can and chooses not to.”

Join me—share the message far and wide—and together we’ll be Carrying Independence.

Ready to discover the untold story of how our founding document survived the Revolutionary War? Visit Carrying Independence to learn more about the novel, or secure your autographed copy at my bookstore.

The Sole Declaration of Independence

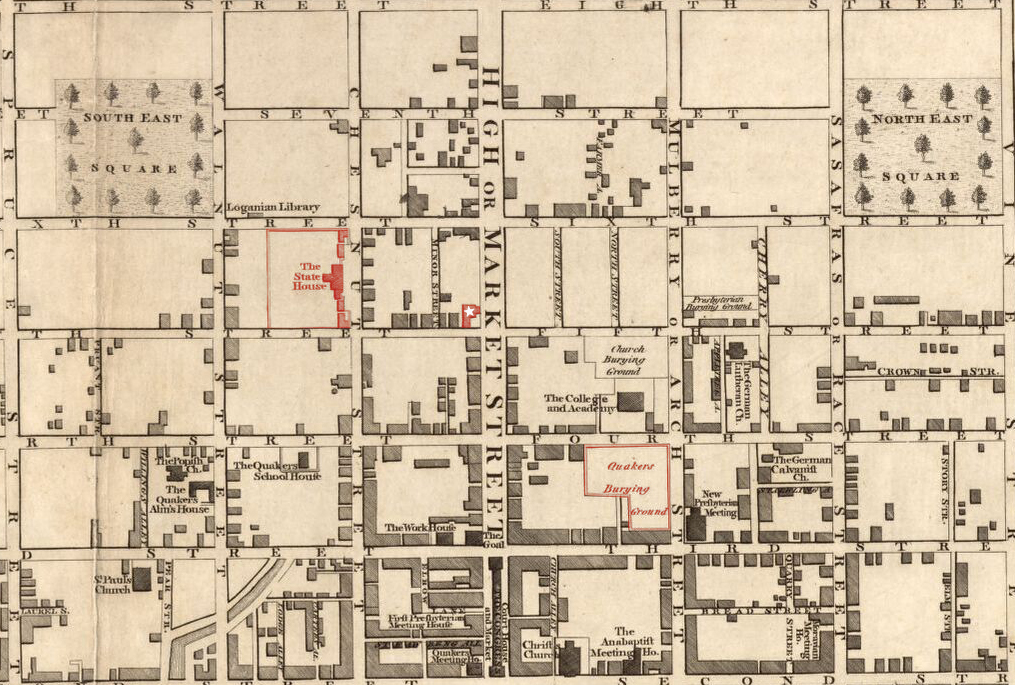

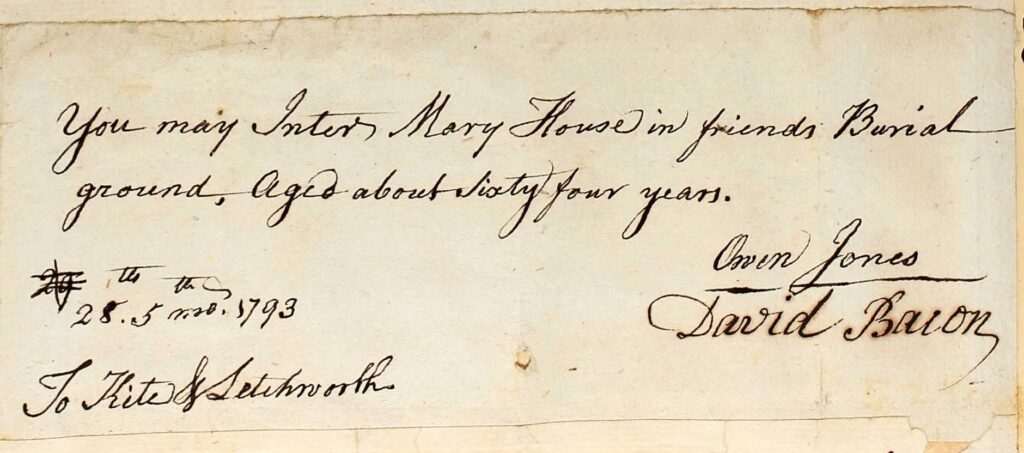

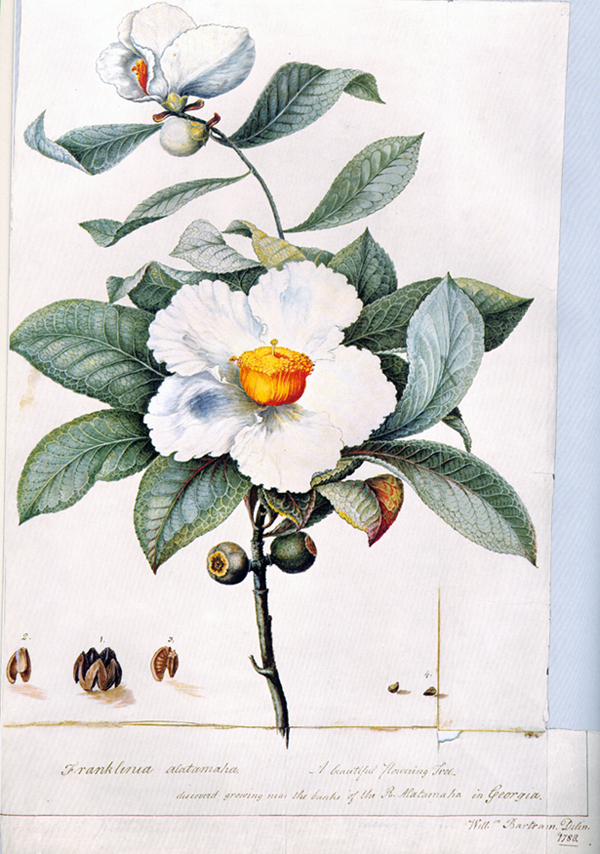

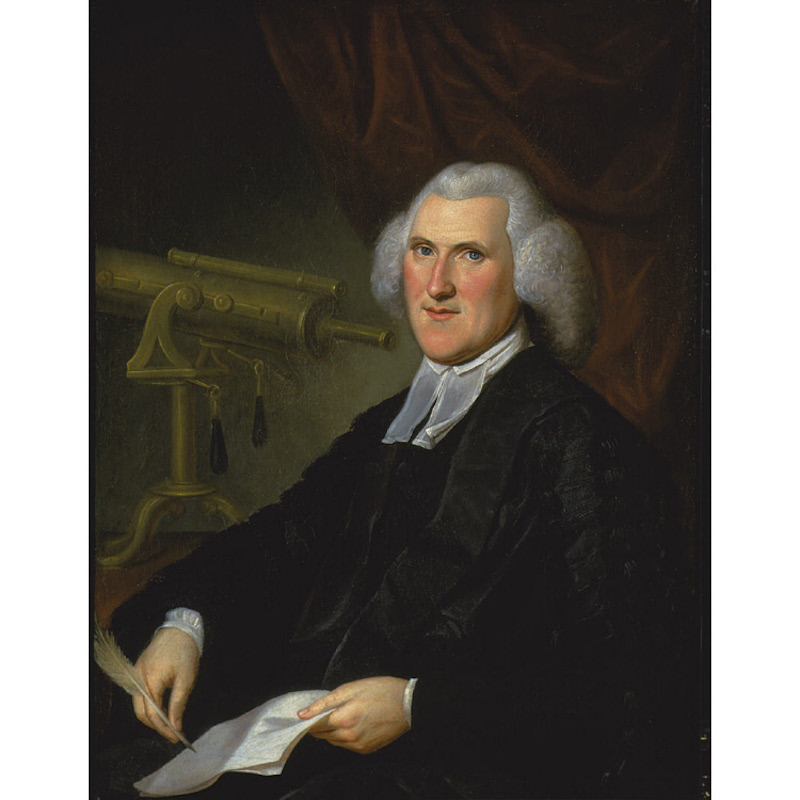

The Sole Declaration of Independence I first encountered John Ewing, on the pages of a 1953 Historic Philadelphia book, published by

I first encountered John Ewing, on the pages of a 1953 Historic Philadelphia book, published by

There is Opportunity in Writing About the American Revolution

There is Opportunity in Writing About the American Revolution