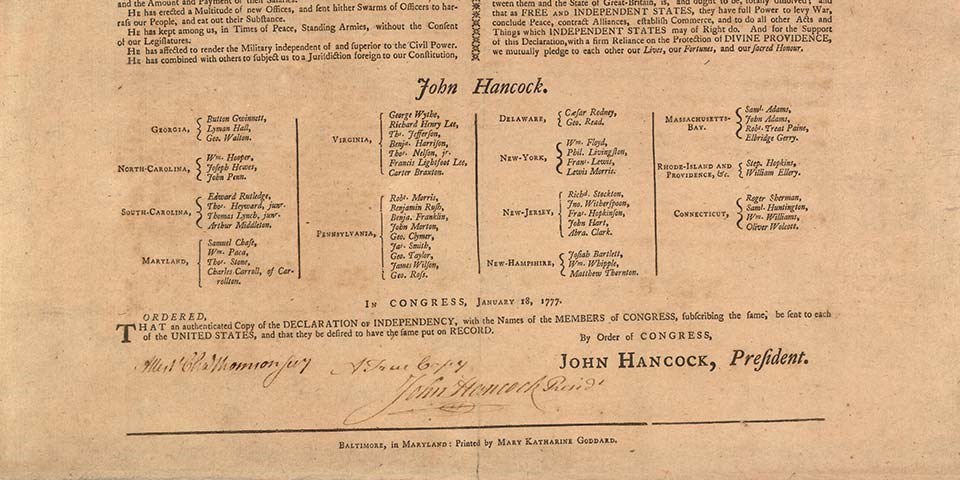

With so many authors now stuck at home, and readers seeking solace in books, I thought it might be fun to give a behind-the-scenes peek into the making of my Revolutionary novel, Carrying Independence. Today, character building.

Character Building for Plotters

Every author has a different method for writing. Some are “pantsers”—those who write by the seat of their pants, building plot, story, and characters on the fly while writing. I am decidedly not one of those writers.

I’m a planner, happily living in that category of writers called, “plotters.” I rough out the plot of a story from beginning to end before I start writing, and adjust as necessary as I research and write. And when it comes to characters, I’ve a worksheet I use.

Character Development Worksheets

Most of my worksheet is unoriginal. Over the years, I read a variety of blogs, books, recommendations, and writing resources, and gathered together what I felt best suited the way I write and think about characters.

Why fill out a worksheet? Written down, I have guidelines to help ensure my characters stay true and grow as they’re supposed to. Then they look, sound, act, or think like themselves and not like everyone else.

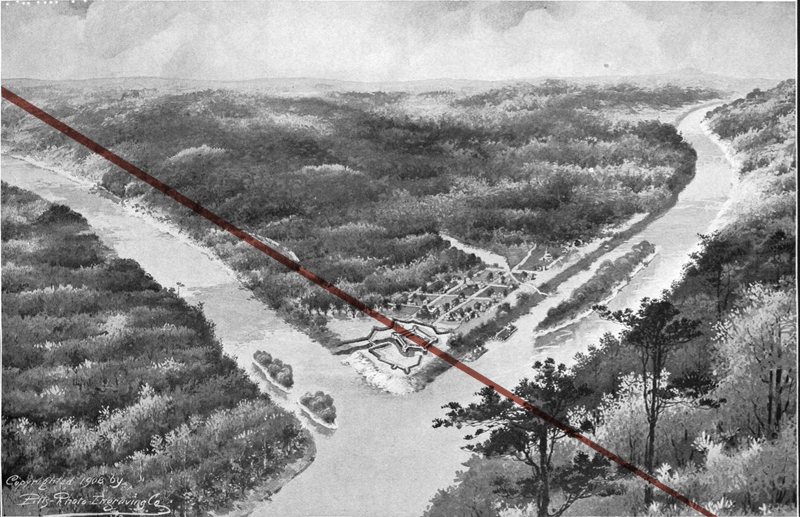

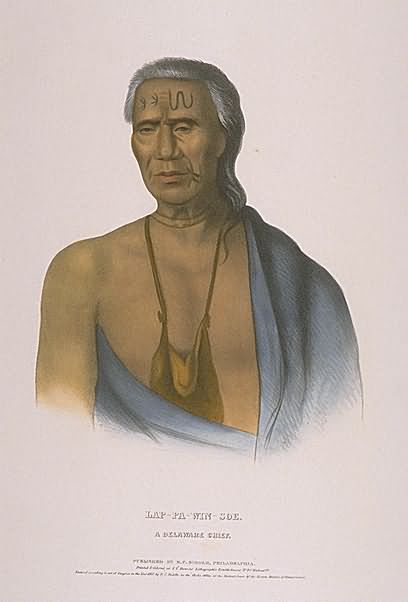

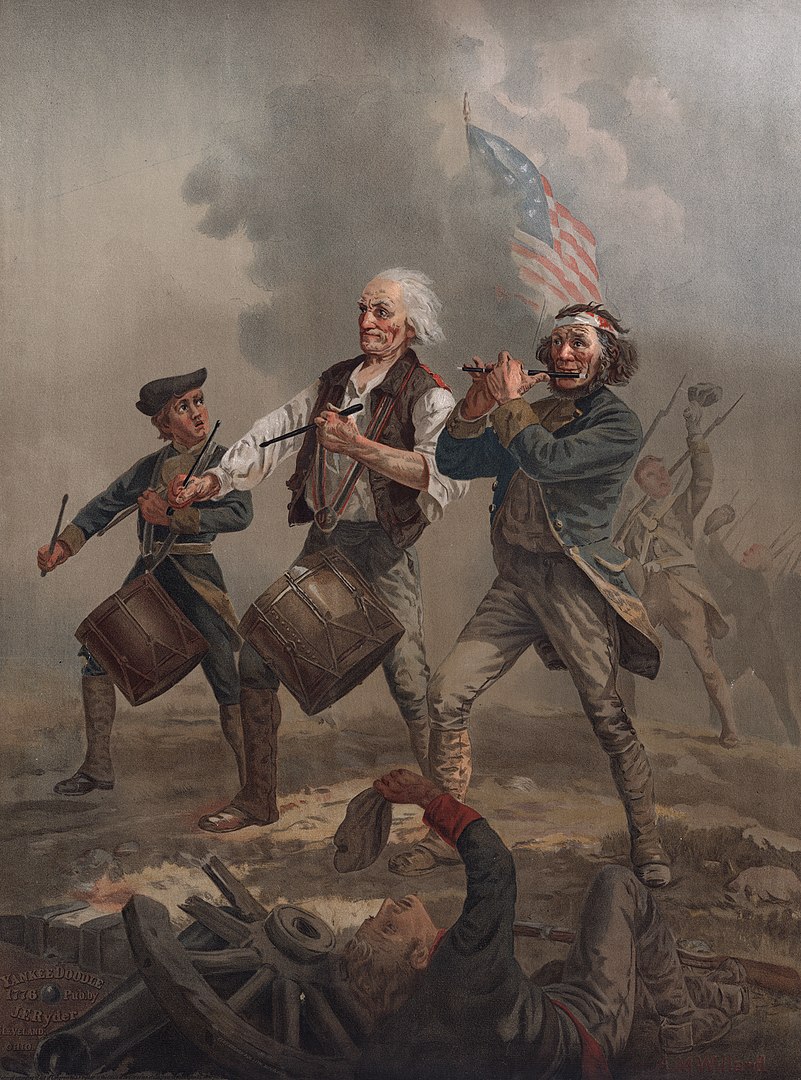

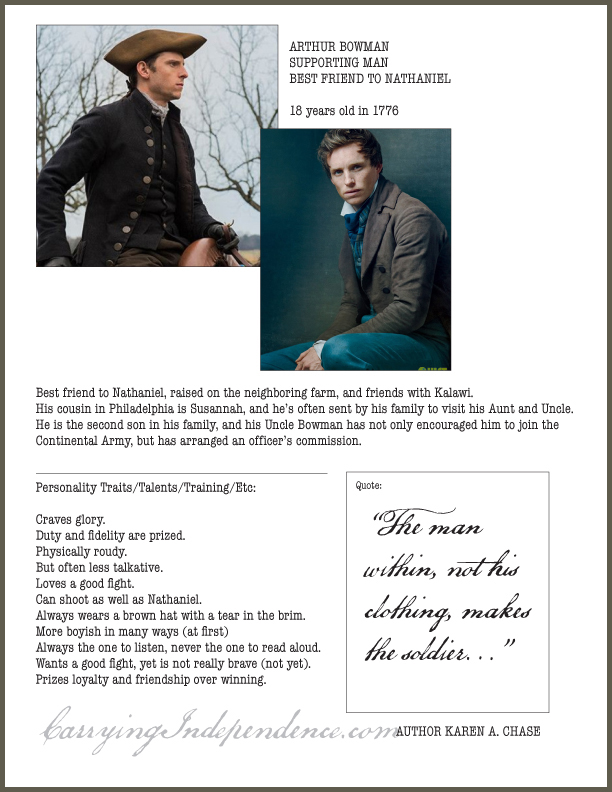

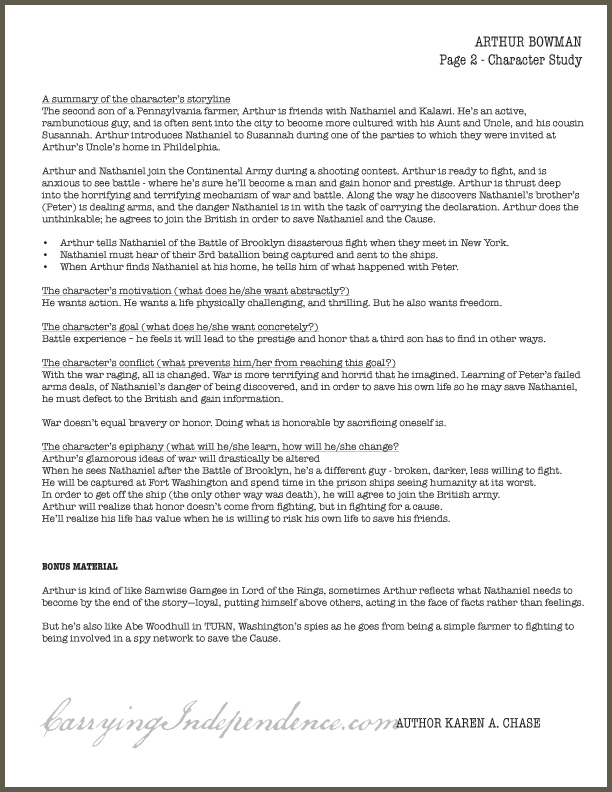

Below is a breakdown of my two-page worksheet. The accompanying images are from the bio I created for my supporting character, Arthur Bowman. You’ll learn much about him from the worksheets. (Note: Grammar and spelling aren’t important in worksheets. These notes are just for the author and perhaps their editor, so please forgive any tiny little errors).

Page One, Basic Character Info

This page has name, age, basic story line, and relationship to main character. At the bottom are bullet-point characteristics. After I’ve written some of the character, I go back in and add a quote from them that I feel captures the person or their thinking.

This page also includes photos of actors I envision for the role. Yes, looking through Google Images and IMDB.com can take an inordinate amount of time, but I find it does help me write the physical traits of a character. (Plus it is SO fun, and every author optimistically daydreams about who would play roles when our books are adapted to film.)

Page Two, The Character’s Story Points

We all want something. Abstractly, we might want love. Concretely, we might want to marry the hottie who lives on the corner. Through a series of questions, I determine what it is my character wants, what they learn along the way, and what prevents them from getting what they wanted. (Characters can’t simply get what they originally wanted at the beginning of a story or they won’t grow enough… but that’s another post in itself.)

Bonus Material for Character Development

For some characters, I might need more detail to keep me on track. This bonus material might be historical information related to the character, like names of places, maps, or images of things they carry. Sometimes it’s their story line written from their point of view in just a paragraph or two. Or, as in Arthur’s bio, it has notes of characters from movies or literature that I hope this character embodies. This section is usually more robust for my main protagonist and antagonist.

Character Bios Can Should Change

Without a doubt, character bios, like my entire plot, are adapted or updated as I work through rewrites. Certainly the time it takes a book to be produced alters these character worksheets, too. Nearly every actor or actress I initially picked outgrew the part I hoped they’d play… sigh. New experiences in my life also helped me deepen characters or their journey. Or as Arthur and his friends say, “On this journey, we each our own way go.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Reader Insights: You can read an excerpt of a scene at City Tavern with Arthur on my website. This scene is early on in the novel, and primarily between Nathaniel and his brother Peter. You’ll lift a pint with Arthur nearer the end, where you’ll see some of his earlier characteristics come out. Carrying Independence is available as an ebook and also in print.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

For more history nerd posts like these, subscribe to the blog. Guest posts are welcomed and encouraged. Contact me for details.